Ok, so I finished this 30 minute essay on time, but looking back on it, I don’t know if I actually answered the question. I sort of did… When discussing the “best” wine in Burgundy, I believe that you MUST incorporate the producer as must as the specific terroir.

*************************

In your opinion, what is the best wine made in Burgundy? If you were talking to a wine novice, how would you explain what is so special (or outstanding, or memorable) about that one particular wine?

Burgundy is an area of such nuance, that it can be completely overwhelming and an exhilarating hunt at the same time. With only two principal grapes, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, and a long history of bottling single, small plots, it is overwhelming how different two wines grown next to each other can taste. But once you discover that those two wines do taste different, there is a lot to explore in the region.

To say what is the “best” depends on your budget and circumstances. There can be best value or best experience. The Burgundian terroir can be either wonderfully translated or completely obscured by the winemaker, so part of the hunt in Burgundy involves producers as well as the specific vineyard site. Therefore, there can also be a “best” Burgundy to choose when you don’t recognize the producer.

Some of the best values in Burgundy are outside of the famed Côte d’Or in the Côte Chalonnaise. This subregion is situated right below the Côte d’Or and while it does not benefit from the limestone escarpment of its famous neighbor to the north, there is enough limestone and different expositions that wonderful Pinot Noirs can be found here as well. One wonderful value is from Dureuil-Janthial, especially their Rully Rouge at about $35 per bottle, is a wonderful expression of Burgundian Pinot Noir. The wine is elegantly balanced between fruit and earthiness that you would expect in Burgundy.

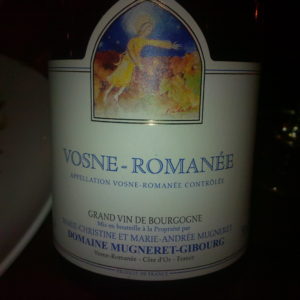

If money is not an issue, look for any of the wines from Mugneret-Gibourg for a completely transcendent experience. The wines that these sisters produce quietly strike an emotional cord for their finesse, length of pure Pinot Noir fruits and spicy complexity with a silky texture that is the ultimate expression of Burgundy. While they don’t produce wines that sell for under $125 per bottle, these are also wines that have tremendous ageability and will evolve to include more of a truffled earth expression in time. Their Vosne-Romanée would be an exceptional wine to track down and try to understand why this is one of the best wines in the region.

As previously discussed (and evidence above), knowing the producer is also an important part of understanding Burgundy and when in a situation where you do not recognize producers (on a wine list or in an unfamiliar wine shop), Chablis AOC can usually provide you with the “best” Burgundy. The grape here is 100% Chablis and at the regional level, there is usually no new oak or heavy lees allowing you to experience the bright and flinty character that is so typical of this area.

Understanding Burgundy is not something that can be accomplished in a weekend and it can be a maddening experience once you start to explore. Starting here with the best of what this region has to offer should help you decide if this area is as special as all the wine geeks say.