The author (Clark Smith of Postmodern Winemaking) has a very technical definition of wine’s structure that might be different than the one you are used to. What is your “go-to” definition of wine’s structure, such as you might use when introducing the topic to a group of wine newbies?

20 minute essay

*******************************

Wines generally have two features: their aromas/flavors and their structure. Within the structure, there are several elements to notice, and it is by identifying these structural elements (along with signature aromas) that wine professionals can judge the quality (via balance and typicity) of a wine. The major structural elements to pay attention to includes body, acid, tannins and sweetness/bitterness.

The body of a wine is its perception of weight in the mouth, the classic example is the ‘weight’ of skim milk versus cream. The body of a wine can give tasters clues as to the climate the grapes were grown in (lighter-bodied wines tend to be from cooler climates and fuller-bodied wines from warmer), but there are also wines whose structure is mainly defined by its body, as in Gewurztraminer, which tend to be fuller bodied at the expense of acid.

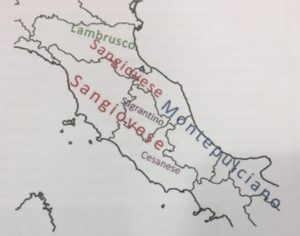

Acidity is among the easiest structural elements a taster can understand. The amount of acidity in a wine corresponds to the amount of saliva the mouth produces. Certain grapes, like Barbera, are known for their high acidity, and while this wine can often be confused for another red cherry aroma Italian wine like Sangiovese, Barbera leads with its acidity, whereas Sangiovese can show both bright acidity and dusty tannins as well.

Tannins are perceived as a drying sensation in the mouth and can be generated from oak ageing as well as from the grape itself. Grapes like Mouvedre or Tannat will have a structure that is defined more by its tannin profile.

Finally, sweetness is part of a wine’s structure, although this can also be altered by the winemaking process. A classic example of sweetness is in a Mosel Riesling where the deliberate residual sugar is used to balance the very high levels of acidity (high acidity being a signature of the Riesling grape). In other parts of the world (as in Australia), Riesling will be finished dry but still showing high acidity because the fuller body of these wines are balanced with the higher acidity creating a balanced wine. Bitterness can also be present in wines, particularly white wines with thicker skins. Wines like Albarino and Gruner Veltliner will show moderate to elevated acidity, respectively, but the signature bitterness of these wines will help create a more firm structure typical of these wines.

Along with learning a wine’s signature aromatics, identifying and understanding the different structural elements of a wine will allow a wine drinker to identify and enjoy (and successfully pair) wines better in the future.